The Major Scale

Why you should learn to use it and how to pick it out anywhere on a guitar

Musical scales is the foundation of all music. Together with rhythm and tempo, scales gives you simple rules to follow in order to make your music pleasurable to any listener.

Basically, a scale gives you a cheat sheet of different notes that will sound great together. This is extremely handy when you want to write your own music, and even more so if you want to play together with other musicians.

To pick out a scale you start somewhere, at any note really, and then you find other notes that sound good together with this point of reference. The note that we start the scale at is what we call the root.

When you look at scales for the first time they can look quite intimidating. Not to mention, on a guitar, there is no easy way to tell by just looking at the guitar which notes are included in the major scale. How envious we can be at piano players for having the C major scale marked out as the white notes!

But once you know the scale pattern on the guitar you just need to find the root note and then you can move the pattern anywhere. This can actually be easier for us guitar players as your muscles will do the exact same movement but at a new place on the guitar neck.

This article will give you a basic understanding of why certain notes are in a scale whereas other are not, and how you can use this in order to create your own music.

The foundation of the modern scale

Some 2000 years ago, a man named Pythagoras sat down with strings of the same thickness and stiffness and divided the strings into logical mathematical relationships. Basically what Pythagoras was doing was to adjust the length of the string in the same way as you do when you press down your fingers on different frets on the guitar.

Pythagoras wanted to find simple, mathematical relationships between notes to get the perfect sound. He started by dividing the string in half.

The halved strings length has the mathematical relationship of 1:2. This gives a frequency of 2/1 which means that when the short string vibrates 2 times, the long string vibrates 1 time. This is the simplest relationship in music.

Because they so often end up in sync, we say that these notes harmonize. In fact, when played together, the long string and the half string sounds like the same note and thus has been given the same name. This is what is called an octave.

If you start your scale at C, then the half string is also a C but one octave higher.

Between the long string and the halved string Pythagoras picked out 7 more simple mathematical relationships. Together with the halved string, this gives us 8 simple relationships, which is why it is called an octave. Octave means eighth in latin.

The second most simple relationship is a string length of 2:3. This gives us the frequency of 3/2, when the short string vibrates 3 times the long string vibrates 2 times. This is what we call a fifth.

The name ”fifth” comes from the place in the scale that this relationship has. The relationship is very simple and one of the most effective note combinations to use if you want to write a song that sounds pleasurable to the western ear.

The simpler the relationship, the more often the notes sync up and thus harmonize. The major scale gives us eight notes that harmonize quite well, and the relationships that are used in western music are; 1:1, 1:2, 2:3, 3:4, 4:5, 3:5, 8:9, 8:15

Why are there 12 frets but only 8 notes in an octave?

As mentioned earlier, you can start from anywhere at the string to pick out a scale. If you for example start at 2:3 of the string and want to get a scale from there, you will sometimes end up at places that were not included in the scale for the full length of the string

To account for this, more notes has to be added. This is why there are no easy way to tell, just by looking at a guitar, how to pick out the major scale. This is also why there are black notes on a piano

The added notes correspond to the 5 extra frets in every octave. In total, there are 12 frets from the root to the octave, and we need to pick out 8 notes.

Because of the way the frets are spaced, we actually don’t get the perfect intervals that Pythagoras calculated. This is because if we had perfect intervals it would be impossible to change keys. We come close though and it is still these mathematical relationships that are the basis for the major scale.

The frets also provides us with a way to tell which notes are in the scale and which notes are not, we just have to learn a simple formula

Note to the advanced learner! The mathematical relationship for a major scale is only 100% accurate when we are in just intonation temperament. In modern music most musical instruments, including the guitar, use 12-TET (twelve tone equal temperament) intonation.

The formula to pick out the major scale

To pick out the major scale you use a formula that is based on how many frets there are between notes in the scale

When we say whole-step, that means that we omit one fret between notes in the scale. When we say half step, it means that the frets directly next to each other are the ones we should use

The formula looks like this: Whole-step, whole-step, half-step, whole-step, whole-step, whole-step, half-step

Example of the major scale

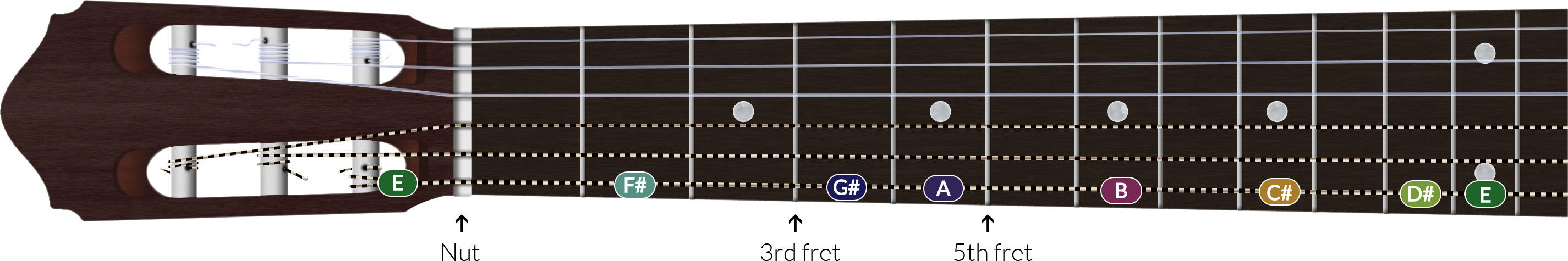

Let's assume that we start with the full length of an open string, this is the root of the scale. We will let this be the 1st position in the scale.

The halved string will also be the root of the scale but one octave up. The halv length of an open string corresponds to the 12th fret. This is the 8th position in the major scale. From there the pattern will repeat itself, so we stop there.

The frequency ratio tells us how often the shorter string vibrates in relation to the longer string. The string lengths and the frequency relationship between the root and any given note in the scale are inverted.

For example, the 2nd position in the scale has a string length of 8:9 relative to the string length of the root. Thus, the frequency is 9:8 relative the frequency of the root. Thereby, the second note in the scale vibrates 9 times when the root has vibrates 8 times.

| : h4 Major Scale Ratios - (Just Intonation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position in scale | String length | Frequency Ratio | E major | Fret Number |

| 1st, root | 1:1 | 1/1 | E | 0 (open string) |

If you want an other visualization of the scale pattern, you can look at a piano. The white keys on a piano corresponds to the C major scale.

As I said before, even though this may be easier to spot the C major scale on a piano, if you want any other major scale on a piano you must include the black keys, thus learning new movements for your hands whereas on a guitar you can just move the exact same pattern to another part of the guitar. You must only know where you have your root.Figure out which note is a C and then start counting, the black keys are omitted so that is a whole-step. Where there are no black keys you get a half step.

How you can use the major scale to create your own music

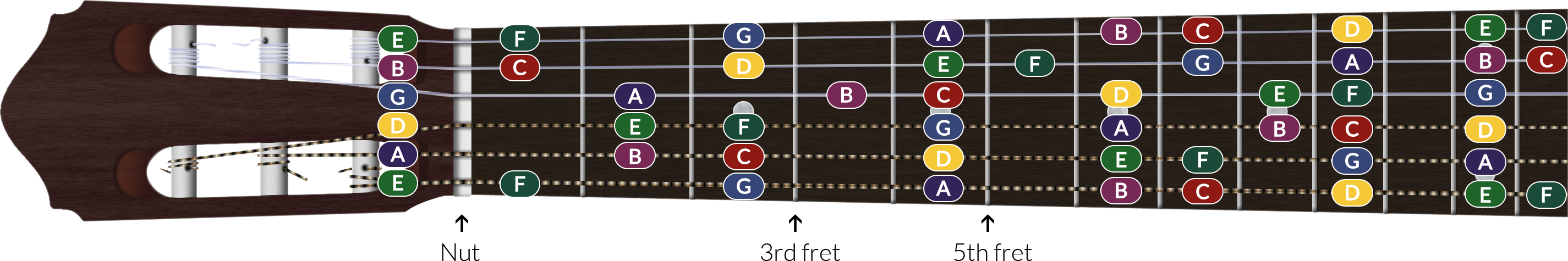

This image shows you how the C major scale looks on a guitar that is tuned with standard tuning. Every note that is marked out on this guitar is included in the C major scale and will thus sound good together.

When you have the guitar in standard tuning, all the open strings are included in the C major scale.

Note: Standard tuning looks like this from the thickest to the thinnest string: E, A, D, G, B, E. Or as a mnemonic: Eddie Ate Dynamite Good Bye Eddie.

Remember though, the simpler mathematical relationship between intervals, the better the interval will harmonize. Thus, C and G arguably sound better together than C and B.

Whenever someone plays music in the key of C, you can play along using these notes. It may seem like a daunting task to memorize all these notes in order to be able to play, but the good news is you don't have to!

You can cheat by remembering where C is located on the guitar and then just remember the pattern: Step, step, half-step, step, step step, half-step.

Or you can use the picture above and find a pattern in it to play along with the music. Find your own patterns and try to make your own music.

It might just be a lucky side effect that you memorize parts of the scale if you use the image and creates your own music using it. Or, maybe you don't memorize the scale but find something that sounds good anyways, it doesn't really matter.

Have fun with the guitar and play from your heart. Everything else will fall into place eventually.